Around the world, governments use tax exemptions and zero-rating (otherwise known as tax expenditures) to provide benefits to companies in the hopes of increasing investment, employment, and economic growth. Yet tax expenditures (TEs) are often opaque, and it is often not clear whether they actually achieve targeted goals. As a result, in recent years, global institutions like the IMF and civil society actors like Tax Justice Network have called on governments to be more transparent about these incentives, and to restrict their use where benefits are not demonstrated. Regular and comprehensive TE reporting is a good practice that enhances transparency. Such reporting should clarify the criteria for administering tax exemptions, deductions, credits, special rates, detail the types of beneficiaries, and assess the economic implication of foregone revenue.

In Kenya, the government spends nearly 3 percent of GDP on tax expenditures, but lack of transparency makes it hard to know what these exemptions are for and whether they have an impact. While the government has recently begun to produce TE reports, these do not meet international standards and do not assess the economic impact of TEs.

Kenya’s National Treasury has published TE reports 2021 and 2022 TE reports. However, these reports are generic, and fail to produce evidence on the impact of the country’s generous tax incentives on the economy. While an estimate of the costs of tax expenditures is provided, there is no estimate of the benefits. The government’s approach to defining the benchmark tax system—that is, what the tax system would look like in the absence of tax expenditures—leads to some tax benefits (including some that are likely costly and deserve analysis) dropping out of the analysis.

At the same time, the benchmark tax system report is not publicly available thus undermining the principle of transparency and accessibility of information. The 2022 TE report only gives a summarized criteria for defining a benchmark tax system, but this summary is not sufficient to know if the general tax regime is beneficial or not when tax relief and exemptions are granted. Moreover, the TE report does not count preferential tax measures such as exemptions, waivers, deductions, or reliefs given to Companies located in Export Processing Zones and Special Economic Zones (SEZ) as tax expenditure hence an under-estimation of revenue foregone. The TE report also refers to a national tax policy that to date has not been finalized as the criteria for defining a benchmark tax system.

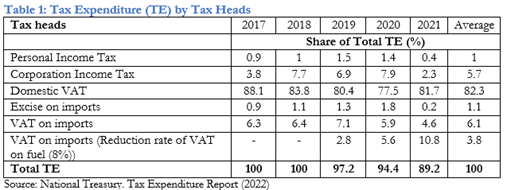

Another gap in the TE report is the failure to disaggregate CIT expenditure into resident and non-resident corporates. This denies the public an opportunity to establish which category of corporates takes the highest TE and why. VAT, on the other hand, is broken down by domestic VAT and VAT on imports as shown in Table 1

Even here, however, failure to break down TEs for VAT on imports and domestic VAT by goods and services makes it hard to assess whether the revenue foregone on some commodities and inputs achieves the goal of easing the cost of living for the vulnerable in society.

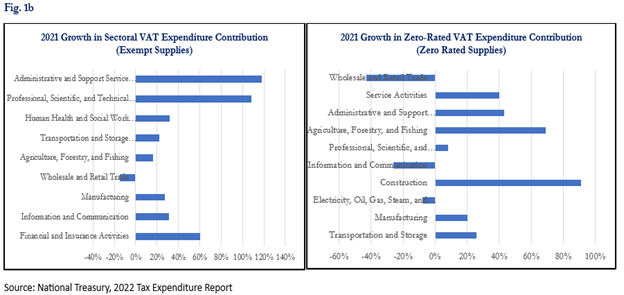

The TE reports reveal that Agriculture, Manufacturing and Construction and Service (Financial and Insurance Activities) are among the sectors that recorded high growth in exemptions and zero-rating to encourage investment and stimulate production (shown in Figure 1b).

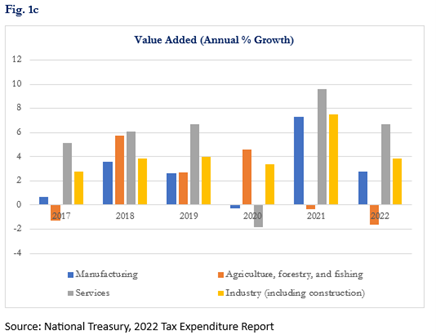

Ideally, a TE incurred today should have a long-term positive impact on the targeted sectors including growth in value addition (net output of a sector after adding up all outputs and subtracting intermediate inputs). It is difficult to assess whether or not this is true, given a lack of transparency in reporting. Moreover, the COVID pandemic has disrupted trends in exports and value addition. At a glance, however, the data suggest a need for more research to establish whether there is any link between TEs, exports and value addition, as there are not clear trend lines demonstrating improvements in exports and value addition over time.

These inconsistencies (see Fig. 1c) signals there could be gaps worth further investigation such as distorted incentives where businesses engage in tax planning strategies to maximize benefits from exemptions, ineffective targeting that result to tax exemptions and zero rating being directed towards sectors or activities that do not genuinely need support for value addition, and misallocation of resources especially when businesses focus on activities that benefit from tax exemptions rather than investing in value-added activities.

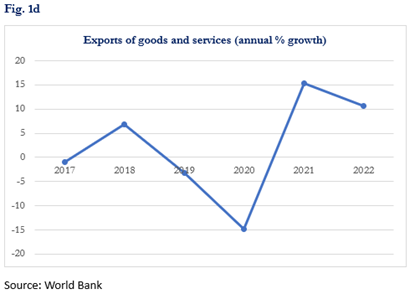

Moreover, there is also not a clear link between export growth and preferential tax measures given to Companies located in Export Processing Zones and Special Economic Zones (SEZ) with a goal to promote exports (see inconsistent trendline in Fig. 1d).

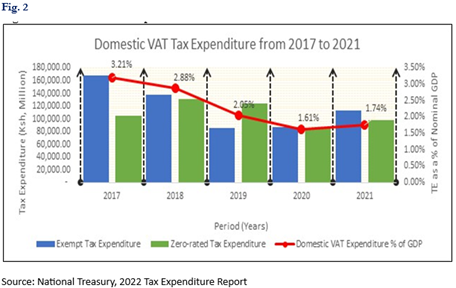

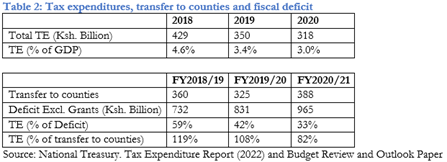

Although there has been a notable decline in TEs as shown in Fig. 2, tax expenditures still account for a substantial share of economic activity. Foregone revenue from these incentives could improve public finances in a country that has been struggling with high fiscal deficits and inadequate transfer to the counties. Evidence from available data (shown in Table 2) establishes that the amount of foregone revenue between 2018 and 2020 as tax expenditure would have been enough to finance transfers to the counties. Or it could have reduced fiscal deficits by more than a third.

In summary, TEs diminishes the available funds for service delivery, necessitates elevated tax rates to generate the same amount of revenue foregone, and/or contributes to an expansion of the budget deficit. The question remains whether the costs are worth bearing. To assess this, the government need to adopt a best practice in making publicly available comprehensive TE reports indicating the beneficiaries and amounts and expiry periods to analyze whether this is so. Such information would facilitate scrutiny and mitigate the risk of abuse by politicians and those close to power. Further, a diagnostic of TEs against policy goals is required to identify distorted incentives, ineffective targeting, and misallocation of resources.

Author Bernard Njiri

Senior Research Analyst

Institute of Public Finance